Robin Lakoff, a linguistics professor emerita at University of California, Berkeley, is one of the foremost scholars on the impact of language on our attitudes and behaviors. Jessica Bennett of the New York Times cites Lakoff as saying, “We are uneasy with the president as ‘she’ because encountering it forces us to have in mind a new conception of ‘president.’” Lakoff’s point, as well as the findings reported by Bennett on new research on language used in the 2016 presidential election, is that the language we hear and use influences our behavior, including who we vote for.

Robin Lakoff, a linguistics professor emerita at University of California, Berkeley, is one of the foremost scholars on the impact of language on our attitudes and behaviors. Jessica Bennett of the New York Times cites Lakoff as saying, “We are uneasy with the president as ‘she’ because encountering it forces us to have in mind a new conception of ‘president.’” Lakoff’s point, as well as the findings reported by Bennett on new research on language used in the 2016 presidential election, is that the language we hear and use influences our behavior, including who we vote for.

Try this experiment, which I have been using for years: simply switch the order of the gender you name first in a sentence. Say and write “women and men” instead of the standard usage of “men and women.” One workshop participant recently said to me, when I put “woman” first in a sentence, “You’re trying to mess with our minds.” He was right. I became aware at some point that when I change the order of the gender pronouns, it does register as “not right” with listeners and opens the possibility of a conversation about unconscious bias. And, if you are like me, you have noticed how much concentration it takes to use gender neutral pronouns like “they” and “them” in reference to gender expansive people who do not identify as either female or male. Our brains don’t have an existing pathway that we can reflexively travel to say “they” and “them.” The same is true with putting “women” before “men” in our language use. But these new pathways can be formed with conscious intention and practice.

Bennett offers other examples of the way “man” is still often the default in the English language, such as maestro, manning the command post, freshman and ombudsman. She cites new research from linguists and cognitive scientists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Potsdam, and the University of California at San Diego who found that during the 2016 presidential race, Americans were reluctant to use the word “she” in the context of a hypothetical president. Even just reading the words “the president, she” caused subjects “considerable disruption” in reading time as their brains “stumbled” over the deeply ingrained bias of “president = he.”

The researchers decided to use the 2016 election as a natural experiment. The hypothesis was that the use of the “she” pronoun in reference to who would win the race would go up or down based on the beliefs of voters about who would win the election. Even though Hillary Clinton was expected to win by a large margin by the research participants, the use of the “she” pronoun did not increase. In a study repeated twelve times between June 2016 and January 2017, the twenty-five thousand participants were asked to predict who would win. While over 60 percent predicted that Clinton would win, the use of the “she” pronoun did not go up.

The researchers conclude that using male language “could indirectly contribute to a culture where women are not typically seen as typical candidates” or leaders. The study’s main author, Dr. Titus von der Malsburg, notes that this could influence elections “because women would have to do extra work to convince voters that they can do the job.”

During the 2020 Democratic presidential primary debates, I remember how it was almost jarring to me when the women candidates would say, “the president, she . . . ” I realize now that they were trying to break through our deep and unconscious bias toward men as leaders. It’s deep. Unfortunately, none of the numerous talented and capable women running for office were successful in breaking through. Let’s all try to change the pronouns we use to be more inclusive as a way to open up more possibilities for who our leaders are in the future. Each time you can put women first by saying “women and men,” you will help move us forward as you disrupt the deep patterns of bias carved in our brains.

Photo by David Everett Strickler on Unsplash

Women have historically been underrepresented in medical research, and it is happening again in the United States with research for a COVID-19 vaccine. Alisha Haridasani Gupta, writing for the New York Times, notes that because data being collected on the virus and in clinical trials

Women have historically been underrepresented in medical research, and it is happening again in the United States with research for a COVID-19 vaccine. Alisha Haridasani Gupta, writing for the New York Times, notes that because data being collected on the virus and in clinical trials  I am always surprised to see research showing that the attitudes of young men about

I am always surprised to see research showing that the attitudes of young men about  Two well-known scholars of gender inequality, Robin J. Ely of Harvard Business School and Irene Padavic of Florida State University, recently published new research in the Harvard Business Review with surprising findings about

Two well-known scholars of gender inequality, Robin J. Ely of Harvard Business School and Irene Padavic of Florida State University, recently published new research in the Harvard Business Review with surprising findings about  Thousands of women in Mexico are regularly being killed as a result of

Thousands of women in Mexico are regularly being killed as a result of  Much attention has been paid in the media to reports that, as a consequence of the large response to the #MeToo platform for reporting sexual harassment, men are withdrawing from mentoring relationships with women. Because scholars have shown that mentoring is an essential element of women’s professional advancement, and media reports of withdrawal are largely based on men’s perspectives and responses, Simmons University researchers decided to examine the actual experiences with mentoring of women protégés in the #MeToo era in their report titled

Much attention has been paid in the media to reports that, as a consequence of the large response to the #MeToo platform for reporting sexual harassment, men are withdrawing from mentoring relationships with women. Because scholars have shown that mentoring is an essential element of women’s professional advancement, and media reports of withdrawal are largely based on men’s perspectives and responses, Simmons University researchers decided to examine the actual experiences with mentoring of women protégés in the #MeToo era in their report titled  Sanna Marin, age thirty-four of Finland, became the world’s youngest sitting prime minister in December 2019. In addition, four of the five party leaders in this coalition government are women, with Marin as the leader.

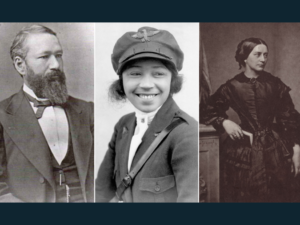

Sanna Marin, age thirty-four of Finland, became the world’s youngest sitting prime minister in December 2019. In addition, four of the five party leaders in this coalition government are women, with Marin as the leader. Courage is a rare human quality, and reading about people from the past who had the courage to break through barriers and act on their convictions is uplifting. I share here the stories of four such overlooked people: Bessie Coleman, Ralph Lazo, Clara Schumann, and Homer Plessy.

Courage is a rare human quality, and reading about people from the past who had the courage to break through barriers and act on their convictions is uplifting. I share here the stories of four such overlooked people: Bessie Coleman, Ralph Lazo, Clara Schumann, and Homer Plessy. I recently ran focus groups for the senior women in an organization to ask what helps and hinders advancement for women in their company. In addition to the usual issues about men taking credit for their work and ignoring their ideas, these women raised a theme that I found especially troubling: they repeatedly asked for training to help them stand up to men who behave inappropriately. It felt wrong to me that these women felt individually responsible to correct deeply embedded societal misogynistic attitudes toward women by getting training to be assertive. Ruth Whippman, writing for the New York Times, points out that

I recently ran focus groups for the senior women in an organization to ask what helps and hinders advancement for women in their company. In addition to the usual issues about men taking credit for their work and ignoring their ideas, these women raised a theme that I found especially troubling: they repeatedly asked for training to help them stand up to men who behave inappropriately. It felt wrong to me that these women felt individually responsible to correct deeply embedded societal misogynistic attitudes toward women by getting training to be assertive. Ruth Whippman, writing for the New York Times, points out that  A primary narrative in family policy in the United States is that parents should have choices. The idea of choice fits neatly within the values central to the founding of the United States—freedom, independence, and individualism. These values assume that people should be responsible for themselves and should “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” In this country we talk about family choice, healthcare choice, and school choice as code words for limited government involvement or small government conservatism, as solidified by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s regarding children. But, as Claire Cain Miller explains in the New York Times,

A primary narrative in family policy in the United States is that parents should have choices. The idea of choice fits neatly within the values central to the founding of the United States—freedom, independence, and individualism. These values assume that people should be responsible for themselves and should “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” In this country we talk about family choice, healthcare choice, and school choice as code words for limited government involvement or small government conservatism, as solidified by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s regarding children. But, as Claire Cain Miller explains in the New York Times,