I had the good fortune to spend a week at the Highlander Institute in New Market, Tennessee, as part of my graduate education. Attendance at a Highlander program was required to complete of my doctorate degree specialization in transformative learning for social justice. At Highlander I learned the truth about Rosa Parks and how change really works.

I had the good fortune to spend a week at the Highlander Institute in New Market, Tennessee, as part of my graduate education. Attendance at a Highlander program was required to complete of my doctorate degree specialization in transformative learning for social justice. At Highlander I learned the truth about Rosa Parks and how change really works.

The Highlander Folk School (which later became the Highlander Institute) was established in 1932 by Myles Horton in the Tennessee hills and initially focused on labor organizing and adult education. According to the Stanford University page about them, “by the early 1950s, however, it shifted its attention to race relations. Highlander was one of the few places in the South where integrated meetings could take place, and served as a site of leadership training for southern civil rights activists.” The Ku Klux Klan menaced them regularly. Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. were among the activists who spent time there building the civil rights movement.

Like most white Americans, I grew up with the myth of Rosa Parks as a simple seamstress, cast as meek, tired, quiet, and middle class, whose single act on a Montgomery bus changed the course of history. Jeanne Theoharis of the New York Times writes that this is a narrow, distorted, and inaccurate view of Rosa Parks. In fact, the truth about Parks is much more interesting and informative about how change really happens.

Theoharis tells us that Parks, born in 1913, had been a civil rights activist for two decades before her historic refusal to give up her seat in the “whites-only” section of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. Before her famous bus stand, she focused tirelessly on voter registration, criminal justice, and desegregation. She attended leadership and movement strategy sessions at the Highlander Institute in the early 1950s where civil rights activists planned actions to challenge Jim Crow segregation laws. Refusing to get up from a seat on the bus was one of many strategies planned, and fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested in March 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a bus. At the time Black Montgomerians decided she was not the right test case. Parks was the next to try it. The combination of her timing and the networks in place, ready to spring into action when she did, resulted in the launch of the successful bus boycott on the day Parks was to be arraigned in court. It took organization and a lot of people to pull off the boycott. Theoharis notes, “The boycott succeeded in part because the Black community organized a massive car pool system, setting up some 40 pickup stations across town, serving 30,000 riders a day. . . . The boycott seriously disrupted city life and bus company revenues.”

Parks and her husband both lost their jobs, received regular death threats, and never found steady work in Montgomery again. Forced to leave Montgomery for Detroit, they struggled financially for the next eleven years. Rosa Parks spent the next several decades fighting racism in the North. In the 1960s and 1970s she was part of the Black Power movement. “Freedom fighters never retire,” she observed about a friend—and she never did either.

Parks fought her whole life against racism, which she saw as a national cancer. Her real story helps us to see our country’s history more honestly and understand that change comes from only disrupting the status quo and persevering to push for change. We must all do our part to get rid of the cancer of racism in this country.

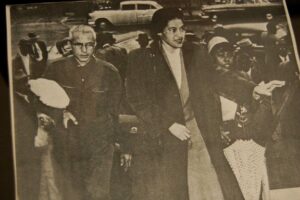

Photo courtesy of Matt Lemmon (CC BY-SA 2.0)