Black feminists in Chicago have been breaking ground as leaders and we can all learn from their strategies and successes. Salamishah Tillet, writing for the New York Times, reports on some of their recent accomplishments:

Black feminists in Chicago have been breaking ground as leaders and we can all learn from their strategies and successes. Salamishah Tillet, writing for the New York Times, reports on some of their recent accomplishments:

- Lori Lightfoot became the first black woman mayor of Chicago in 2019.

- In 2016, Kim Foxx, a black woman, became the city’s top prosecutor.

- In May 2015, black feminist activists pushed Chicago to become the first city to award reparations to people who survived police torture in the 1970s and ’80s.

- Rahm Emanuel, the previous mayor, decided not to seek a third term as mayor after black women organized a citywide campaign against him.

- Thanks to black feminist activists, Illinois became the first state in the Midwest to approve a path to a $15-an-hour minimum wage.

Tillet highlights a four-point model for change used by the black women in Chicago that can be a guide to change for the rest of us:

- Blend activism and the academy—Organizers and professors at many universities in Illinois work together to ensure that community activists and young black people work together and listen to each other. Young black people who feel engaged and empowered affect change. Their engagement can make the difference in elections and policy changes.

- Work across generations—Older feminists encourage young activists to be at the forefront and utilize their expertise, while older feminist activists provide guidance from the sidelines.

- Share power—The black feminists of Chicago encourage many local leaders to emerge rather than allow a single charismatic figure like Louis Farrakhan or Jesse Jackson to set an agenda. People show up for each other’s campaigns rather than align with only one candidate. People show up for each other’s issues as well.

- Work on several issues at once—Collaboration that brings focus to the intersection of issues such as low wages, police violence, and the recent murders of black women and girls is a critical strategy. For example, in 2015 after Black Lives Matter of Chicago organized a rally outside of a McDonald’s to stand with food workers striking for a $15 minimum wage, they all marched to a nearby police department to demand the firing of a police officer who shot an unarmed bystander. This last strategy has always been a hallmark of black feminism—a focus on the intersection of sexism, racism, classism, and other forms of oppression.

Potential presidential candidates have a lot of good reasons to court the support and votes of black feminist activists, whose proven track record of successfully organizing for change is formidable.

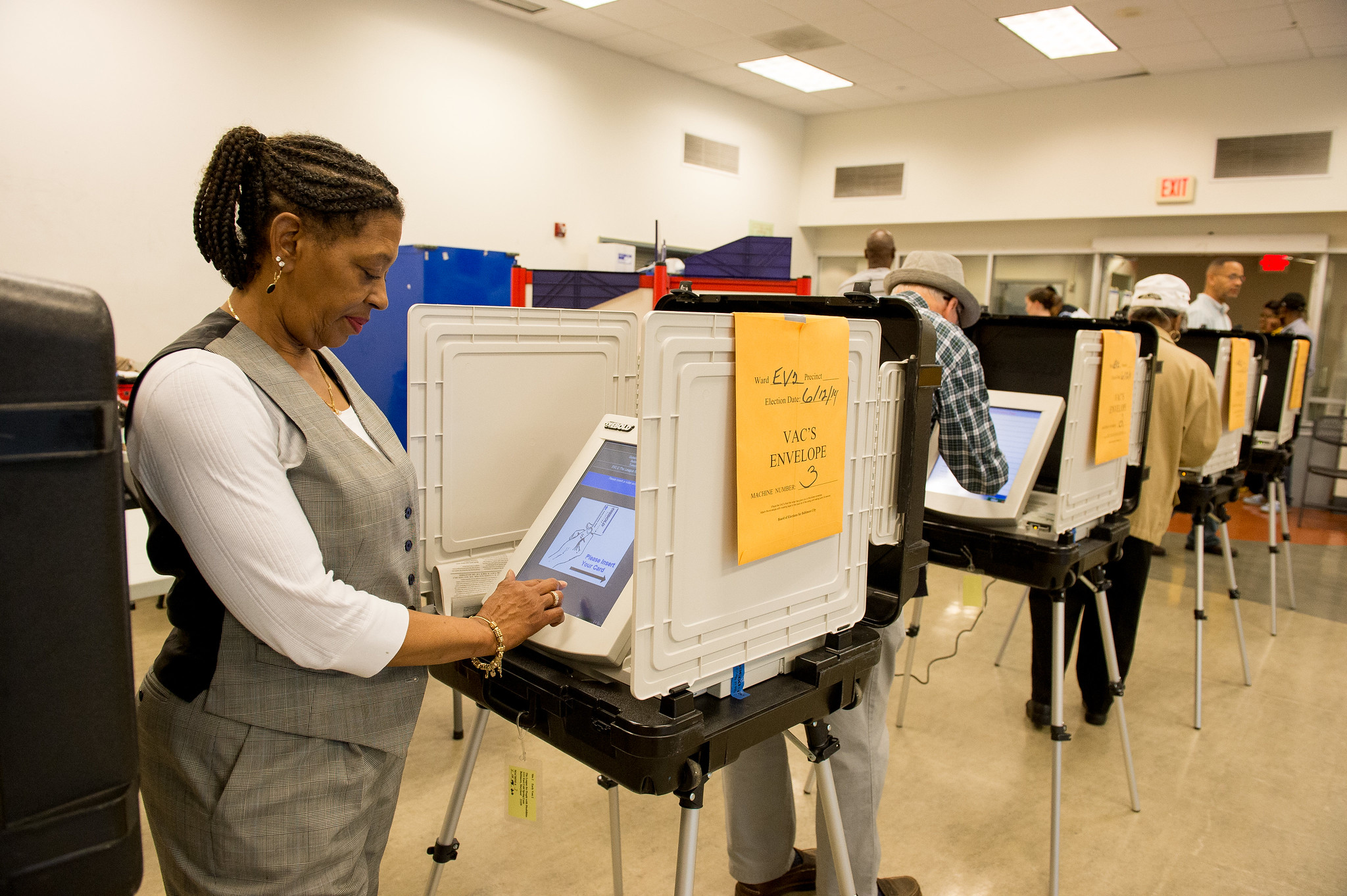

Photo courtesy of Johnny Silvercloud (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Donna Brazile writes in

Donna Brazile writes in