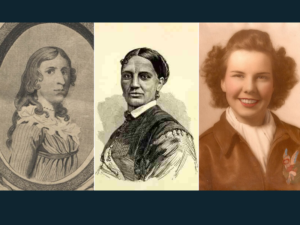

I find it inspirational to read about women in history who I have never heard of but who have accomplished amazing things. Thanks to attempts in recent years by the New York Times to make amends for not acknowledging these women at the time of their deaths, their belated obituaries are now published from time to time. Here are a few of these women:

I find it inspirational to read about women in history who I have never heard of but who have accomplished amazing things. Thanks to attempts in recent years by the New York Times to make amends for not acknowledging these women at the time of their deaths, their belated obituaries are now published from time to time. Here are a few of these women:

Elizabeth A. Gloucester (1817–1883)

Steve Bell writes that “Elizabeth A. Gloucester was considered by many to be the richest black woman in America at her death at age 66 on Aug. 9, 1883.” Gloucester built her fortune, the equivalent of about $7 million in today’s dollars, from owning and operating fifteen or more boarding houses in the New York area, including the elegant Remsen House in Brooklyn Heights, which she purchased for $3 million in today’s dollars.

Gloucester and her husband contributed financially to antislavery activist John Brown, who stayed with them whenever he was in New York. Gloucester also led efforts to raise money for New York’s Colored Orphan Asylum.

Dorothy Olsen (1916–2019)

Dorothy Olsen, born in 1916 on a farm in Oregon, dreamed of flying from an early age after reading a biography of the World War I flying ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen. Sam Roberts writes that Olsen saved money from teaching to pay for flying lessons. When World War II broke out, she was one of 1,074 women to complete army air force training and join the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), the first women to fly military aircraft for the United States. Roberts notes that the WASPs collectively flew an estimated 60 million miles, and Olsen herself flew sixty-one missions. She was also one of only a dozen women certified for night flying.

Always considered civil service employees and not military personnel, the WASPs had to pay for their own food and lodging. Olsen recalled, “When the war was over I was fired, just like that.” The WASPs were finally recognized as veterans, eligible for benefits, in 1977.

Claude Cahun (1894–1954)

Lucy Schwob, born in 1894 in France, decided she would rather be called Claude Cahun in a protest of gender and sexual norms in early twentieth-century France. Joseph B. Treaster writes that Cahun devoted her life as a writer and photographer to the “exploration of gender and sexual identity.” Cahun lived before our current understanding of gender identity and gender-neutral pronouns. Cahun would most likely have preferred “they/them/theirs” as pronouns and explained that “neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

Cahun and her lover, Marcel Moore, engaged in small acts of sabotage against the Nazi occupation of France. They were caught and sentenced to death but were freed when the war ended.

Elizabeth Keckly (1818–1907)

Nancy Wartik tells the amazing story of Elizabeth Keckly, who was born enslaved in 1818, bought her freedom, and eventually became the friend and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln during her years in the White House. Keckly survived years of savage beatings and rapes during her enslavement before starting her own business as a seamstress. She was able to buy freedom for herself and her son from her owners for the sum of $1,200 in 1855. A talented seamstress, she moved to Washington, DC, and was in high demand. Mary Lincoln hired her to make the gown she wore to her husband’s inauguration festivities. Keckly soon became a friend and confidante to Mary Lincoln.

After President Lincoln’s assassination, Keckly wrote a memoir of her life called, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House. Keckly became one of the first African American women to publish a book. Her sympathetic but honest portrayal of the Lincolns’ domestic life angered Mary Lincoln, who severed their relationship, but the book remains one of the most important slave narratives and accounts of daily life in the Lincoln White House.

Deborah Sampson (ca. 1760–1827)

The true story of Deborah Sampson, summarized by Alison Leigh Cowan, is a little known tale of “a woman who stitched herself a uniform, posed as a man and served at least 17 months in an elite unit of the Continental Army.” Details of Sampson’s military service recently came to light with the discovery of a long-forgotten diary recorded more than two hundred years ago by a Massachusetts neighbor of Sampson.

Enlisting in May 1782, Sampson is one of few women to take on a combat role during the American Revolution. Her secret went undetected until she fell ill in Philadelphia and was found out by a doctor in 1783. Dressing as a man was illegal in Massachusetts, and she fought for years to get back pay for her service. Paul Revere and John Hancock both took up her cause and helped her get partial payment after the war.

Isn’t it great to know about these women? I hope you enjoy reading about them as much as I did.

Photos are in the public domain and are courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.